ICE Detention, Dialysis, and Ethics

Purpose and Scope

This is not a partisan post, although it may read like one. This is a post about medical ethics and what happens when public policy and political climate ultimately control access to life-sustaining medical care for society’s most vulnerable people. I am writing this for the nephrology community at large.

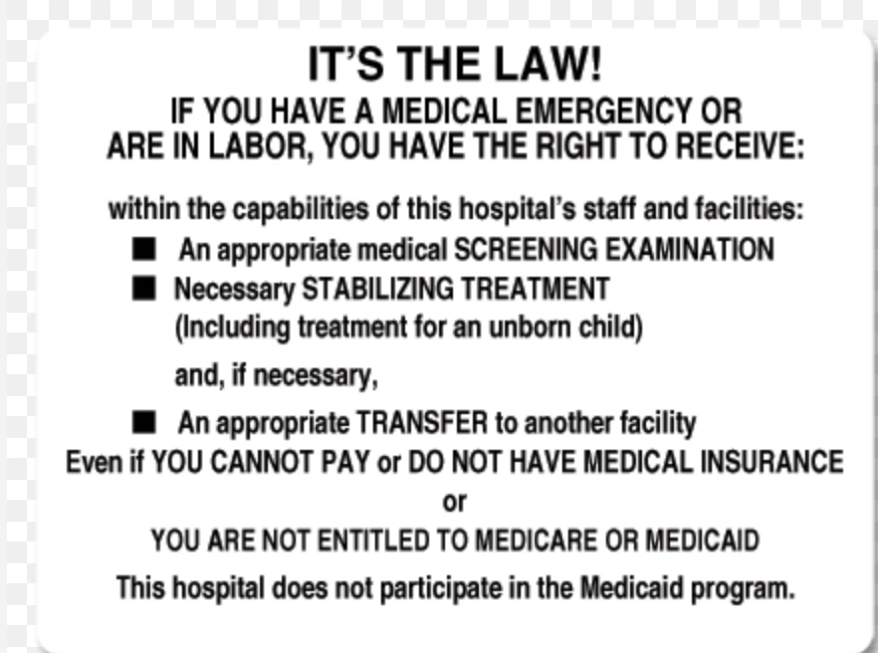

In the U.S., protections have existed for all critically ill persons since 1986 under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). We must have discourse and not allow ourselves to be complacent when humanitarian protections are threatened. We have a duty and a responsibility to respond.

There are many things I could write about the current state of the US immigration enforcement system and policies. I have a lot of strong thoughts and feelings, as many do. However, I want to focus on a glaring problem that specifically impacts kidney patients who are currently held in ICE detention: a serious lack of medical continuity.

I want to be very clear…given current conditions, the risk of death for any person with ESKD detained in ICE custody is absolute. And the nephrology community needs to be aware of this.

Not About Worthiness

This problem is not about who “deserves” to be in the United States or anyone’s definition of legality, borders, or citizenship. The subtext of what is happening in immigration facilities right now should concern all of us very gravely because it reveals how fragile access to life-sustaining care can be in our country.

Medical fragility does not end when handcuffs close around wrists, and a person is whisked off to…who knows where? Regardless of where someone “deserves” to be, do they not still also deserve their Creator-endowed inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? (Asking for a founding father...)

Dialysis Is Non-Negotiable

Renal replacement therapy of any kind is not a routine chronic treatment. For people with ESKD who are dependent on dialysis, therapy requires continuity, is non-negotiable, and it is extremely time-limited.

There is no safe way to pause or defer treatment for a couple of days to sort out legal issues. There is no safe and immediate substitute for dialysis with a more conservative (or less expensive) therapy.

It’s well known and documented that missed, shortened, or delayed dialysis leads to predictable physiological consequences that occur within days and drastically increase the risk of death. The symptoms of inadequate dialysis are the same as those for “end-stage” kidney failure.

Dialysis adequacy, as defined in the U.S. already represents a floor (a minimum) instead of a ceiling (true renal replacement). The “routine” two-day treatment gap endured by most U.S in-center hemodialysis patients is already associated with a higher risk of death. There is no “buffer” on dialysis, 72 hours without treatment is about the point of criticality.

Detention Is Inherently Medically Disruptive

I would personally have an extremely difficult time coping with the stress, exhaustion, and physical demands of a detainment. I have autoimmune arthritis and take medications to keep my immune system suppressed to prevent disabling disease flares. Rapid withdrawal from these medications would switch my immune system into hyperdrive, and I would soon lose the ability to walk. I would be in excruciating pain exacerbated by the confusion and upheaval of arrest, transfers, transports, processing, facility shifts, lack of communication, poor conditions, lack of adequate food, warmth, water, etc. For me, those disruptions would be panic-inducing, physically crippling, administratively maddening, and immunologically dangerous.

For a person dependent on dialysis, these conditions are all of the things they are for me…and are also immediately life-threatening.

Estimating the Scope of Impact

ICE does not report how many detainees have chronic illnesses or the nature of their illnesses. In the absence of official and verifiable data, the best I can do is to conservatively guess how many people with ESKD may be in ICE custody.

Per the USRDS, there are more than 808,000 people in the U.S . living with ESKD and 68% of those are dialysis dependent. In 2021, it was estimated there are between 5,500-8,800 undocumented ESKD patients.

There

are currently approximately 66,000

people in ICE custody. Estimating that a conservative, 0.2% may have

kidney failure,it is possible for there to be ~130 people with

dialysis-dependent ESKD in ICE detention at this very moment.

This number could be off for many reasons, but even if there is

just one person, the legal, ethical and clinical implications

are the same.

This number could be off for many reasons, but even if there is

just one person, the legal, ethical and clinical implications

are the same.

NOTE: My estimate does not include people with late-stage CKD, undiagnosed CKD, medically managed ESKD, or a transplant. Even if I over-shot by 100 people, there may be hundreds more who are medically vulnerable and at risk of rapid decompensation into chronic dialysis dependence currently in detention. The actual number of potentially affected people is very likely higher.

Emergency-Only Dialysis Is Not Safe

As of 2022, about 20 U.S. States provided emergency Medicaid for undocumented immigrants requiring dialysis. Of those 20 states, only 5 will cover a kidney transplant.

For undocumented patients outside those states, lack of medical coverage often forces reliance on emergent dialysis under EMTALA which is provided only when a person becomes critically ill from uremia and presents to an emergency room for treatment. After the treatment, the patient is discharged only to return in a few days when they are again dying, so the process can be repeated.

This model of care for those needing dialysis treatments is associated with dramatically higher costs, increased risk of hospitalizations, morbidity, mortality, and trauma. All of the bad outcomes are caused by the relentless see-saw between relative medical stability and outrageous metabolic derangement.

Once these same under-treated and undocumented patients are detained, their reliance on emergent-dialysis is even more imminently precarious because they are starting off teetering on criticality as a baseline.

The treated undocumented patients may have their 72 hours, but who is assessing these medically fragile people and determining whether their conditions in detention are at all appropriate? I really question that clinical judgement.

From a nursing perspective, providing a chronic therapy (like dialysis) on an emergency-only-basis violates every common-sense approach to chronic disease management. It also violates the ethical principle of non-maleficence.

These Are Not Hypothetical Risks

There have been several cases reported in the news about deprivation of basic medical care for ICE detainees and a few have specifically mentioned dialysis patients.

One story that stood out to me that of Williams Javier Toro Enamoraldo, a 27 year old man from Honduras. He has dialysis dependent ESKD and was detained in November while driving to his regularly scheduled dialysis appointment in Charlotte, NC during “Operation Charlotte’s Web.”

After he was stopped and arrested, Mr. Enamoraldo was not taken to dialysis. Instead, he was put into a van with other detainees and taken to a facility nearly 400 miles away in Georgia. He was sick by the time he arrived. He asked to go to the hospital but was denied.

The next day, he was allegedly offered a dialysis treatment in exchange for signing a voluntary deportation order. He was told he could sign and live, or not sign and die. Ultimately, Mr. Enamoraldo signed the form and was taken to the hospital for a short emergency treatment. I have been unable to find any recent updates on this case, all current reports state he is still in ICE custody but I was unable to locate him in the ICE system.

Another story that struck me was that of José Gregorio, 43, from Venezuela. Mr. Gregorio was in Illinois (one of the 5 States that allows for both dialysis and kidney transplantation under emergency State Medicaid) preparing to donate a kidney to his brother, José Pacheco, 37, when he was apprehended by ICE on March 3, 2025. Mr. Pacheco came to the U.S. in 2022 seeking asylum. His case is pending, and he is unable to leave the United States to receive a kidney transplant from his brother elsewhere, because it risks voiding his asylum application.

Mr. Gregorio had no plans to stay in the U.S permanently and would like to return home after donation, but the process to surgery can take up to a year. Last year, the family pled for humanitarian parole as Mr. Gregorio was willing to altruistically donate a kidney to help. He was granted temporary release from ICE detention in April 2025 and successfully donated to his brother in August, 2025. I have been unable to find any updates on this case since then.

I feel like the takeaway from these cases, and others like them, is that this is not a hypothetical risk. These are real people. This is really happening, and patient lives are already being risked. These are not outlying circumstances, they are glaring red-flag warnings of what will happen next if these problems are not strongly addressed.

Legal and Ethical Obligations

I am a nurse, not a lawyer. So please excuse my armchair quarterbacking, but as I understand current policy, ICE must provide, facilitate, and pay for continuous medical care for detainees.

There is no framework in ICE medical care standards (or anywhere else) that allows for legal coercion to be utilized as leverage for life-sustaining medical care. Forcing a patient to choose between deportation and untreated organ failure is not a consensual choice. It is duress.

Incarceration for a crime in the U.S. does not remove the right to dialysis access. Convicted felons within the U.S. penal system receive scheduled outpatient dialysis treatments on similar schedules and to the same standards as the general population. Our government has the same obligation to the ICE detainees.

Humane Alternatives

If adequate medical care standards cannot be met safety in detention, then detention itself is inappropriate. We must follow the rule of law. Possible options might be medical parole or release, community-based monitoring, guaranteed continuity of dialysis care prior to any transfer or relocation, and full adherence to all existing medical and legal standards.

We must always protect life, and as a society, our protection must be extraordinary when the government itself has assumed custody over a human being.

These situations should alarm us all. What does it say about a society when individual survival depends on citizenship status? What happens to life sustaining care when legal status has the ability to fluctuate? Dialysis is treated as a right for some and a conditional emergency for others. That should be unsettling to everyone in our community who understands what dialysis actually is and what it does.

New Developments

Since I began drafting this blog, new reporting emerged further accusing ICE of severe medical neglect within detention centers. Shockingly, all payments to third-party medical providers were abruptly suspended on October 3, 2025. Since then, ICE has stated it has “no mechanism to provide prescribed medication” to detainees and is also, “unable to pay for medically necessary off-site care.”

Among the specific services ICE states they are unable to facilitate are, “dialysis, prenatal care, oncology and chemotherapy.” Per an ICE release in November, this is a “dire emergency” that needs to be immediately reconciled. Additionally, ICE estimates that claims processing will resume as early as April 30, 2026 using a new online-only system.

Medical providers have been instructed to hold all claim submissions in the interim.

I would love to hear your thoughts about these matters.

Comments

Brittany Morris

Feb 19, 2026 2:48 PM