Cannulation for Solo Home Hemodialysis: My Technique

Cannulation (needling, sticking) is the act of establishing a “canal” between an arterialized vein (the fistula or graft) and the system of blood lines that allow blood to be circulated between the patient and the dialysis machine. Typically, needling involves piercing the skin and wall of the blood vessel (fistula) with a hollow needle attached to a 40 cm length of plastic tubing, which in turn is designed to attach to the bloodlines.

Patients who are trained to develop “Buttonholes” stick the same location repeatedly to attain a re-usable “tract.”

Those using the “Rope ladder” method insert needles over as many locations as possible along the length and breadth of the fistula.

Both methods have pros and cons, and it is up to the individual in consultation with the clinic to develop skill in one or the other technique. In the case of a very short (or contorted) fistula the Buttonhole method finds preference, while bearers of straight, prominent fistulas (figure below) may prefer the rope ladder technique.

Both methods have pros and cons, and it is up to the individual in consultation with the clinic to develop skill in one or the other technique. In the case of a very short (or contorted) fistula the Buttonhole method finds preference, while bearers of straight, prominent fistulas (figure below) may prefer the rope ladder technique.

The Fistula

There are 13 cm of stickable access along the length of the fistula pictured. Though no longer visible near the armpit, the vessel’s location can be detected by palpation (pressing with the fingers) and it can be cannulated right up to the dotted line indicated.

Development over its 3-year career has lead to broadening, thickening and strengthening. Thus at 3 cm width, cannulations are not confined to running up and down the length of the fistula but can use entry points across its breadth. (See the ****). Spacing cannulation entry points 1 cm apart means 52 locations are available. At 8 sticks per week (i.e., 4 treatment sessions) that leaves 6 weeks recovery before a previously stuck location is re-visited.

Clinics agree that cannulation spread over as much of the fistula as possible ensures even development of fibrous tissue attendant upon healing. This minimises weak spots and reduces the risk of aneurisms.

Wet Stick

Some dialysers prefer the use of “wet stick” cannulation primarily to reduce the risk of clotting in the needle or tubing. (Though, most find that syringing 5 mL of saline into the needle line after allowing flashback to reach the Luer cap eliminates clotting). A wet stick involves filling the needle and needle line with saline via syringe, leaving the syringe in place, then cannulating. A disadvantage of wet sticks is that the needle tip’s progress is uncertain because of the absence of flashback.

Teardrop Cannulation

The idea of lubricating the needle’s passage to minimize friction is certainly appealing and this is what Stuart Mott had in mind when he devised inserting a mL or two of saline into a buttonhole’s cavity just prior to introducing the blunt needle. Patients often report struggling to get the needle into position when buttonholing and find relief in this method.

Plastic Cannula

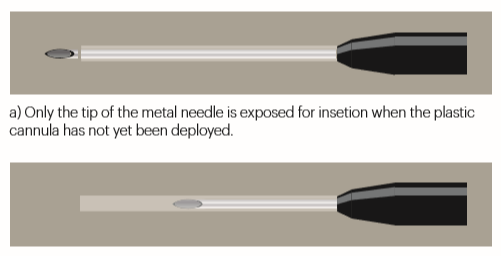

Whilst not yet readily available in the US (and I understand very expensive), plastic cannulas are finding favour elsewhere (eg Australia). The idea is appealing: a soft, flexible tube drawing and returning blood quietly in the access, eliminating the risk of infiltration. Plastic cannulas are especially useful in the case of elderly or agitated patients and those who wish to sleep—with reduced needle anxiety. There is however the barrier of a steep learning curve in their use. In one Australian clinic the staff took 12 months longer to be trained than anticipated, whilst some members were initially reluctant to abandon the conventional and trusted method.

After insertion of the plastic cannula into the vessel, the metal needle is retracted into the automatic safety device; only the plastic cannula remains in the vessel.

SECURING METAL NEEDLES.

Reports of bloody nocturnal interruptions are not uncommon, especially in the early nights of sleeping on hemodialysis. Maximum security and comfort are required and some go to great lengths with sophisticated taping, more and more tape, security sleeves, and blood leak alarms. The method below could be termed a “transition” one as it is easy to set up and serves adequately for daytime dialysis.

Clinics agree that the so called “chevron fold” provides a secure steadying of the needle whilst serving as an initial application of tape.

The tape is slid (sticky side up) under the needle hub.

It is then folded and crossed over before being pressed down firmly on the skin.

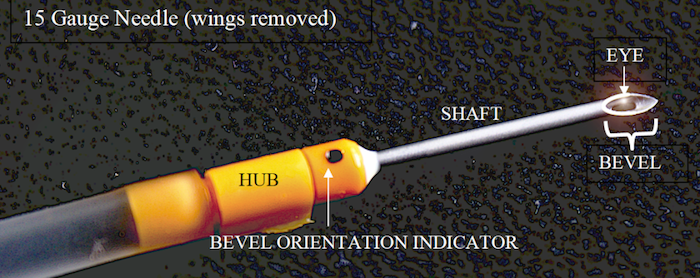

For a solo dialyser, negotiating the wings to achieve this with one hand is a frustration. One solution is to remove the wings, use narrower tape, and encircle the needle hub completely before cannulating. “Touch cannulation” (gripping the tubing instead of the wings) follows. This technique allows better observation of flashback, more direct line of entry between hand and needle, as well as greater sensitivity when probing for the “best spot” for a needle’s destination.

Spreading the sites: cannulation with shallow entry on the inner side of the fistula.

Tape is wrapped firmly around the needle hub before being pressed down to ensure maximum adhesion.

The chevron fold completes the basic taping. Vertical strands and encircling tape to follow.

Comments

S Innoue

Jan 27, 2020 11:07 PM

Thank you.

John Agar

Dec 27, 2018 11:21 PM

One additional layer to skin and vein wall that I personally think matters is the thickness and composition of the subcutaneous (under-skin-dermis) layer = a combination of elastic fibres, fat, mast cells (immuno-modulatory cells) and collagen. It is a layer whose depth (or traversible width) and structure may be a player in the acceptance of, and reaction to, things (like access needles or cannulae) that ‘invade’ or ‘traverse’ it.

This is just my personal opinion as we know so little, really, about some of this stuff.

But, these musings do not, nor should detract from a great post, well said and well described.

Stuart mott

Dec 29, 2018 12:48 AM