Two for the Road: Seeing the World, Living with a Chronic Illness

Authors' note: This is the first of a series of blogs about our adventures traveling in Europe together in 2019. They will appear here on the third Thursday every month, and will eventually be compiled into a book entitled: Taking Chances, or How to See the World Living with Chronic Illness.

DavidHenning and I have been avid travelers most of our lives. Living on modest incomes, we prioritized travel over other life amenities, and often used air reward mileage and job perks to pay for parts of our trips, especially those overseas.

It all started for me one Easter weekend with a family train trip to New York City when I was twelve. I planned the entire trip, and have been doing so ever since. Every time I take a trip to a foreign country or one of the 50 states for the first time, it's like getting another academic degree.

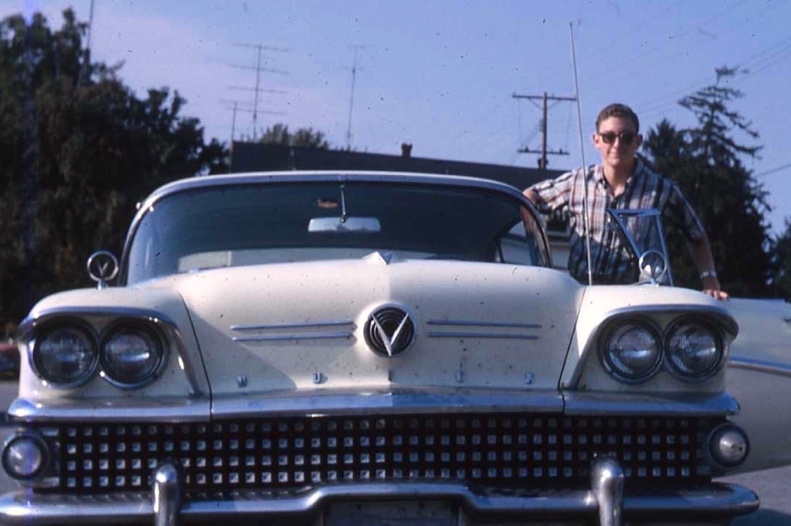

I began to travel in earnest when I was seventeen. My dad had given me an old family car, a big white 1957 Buick Special, and off I went every summer with a friend or two to Cape Cod, Gettysburg, and Washington, D.C. In college, I worked summers for the Dean's Office and led tours all over the East Coast and Eastern Canada. To this day it's hard for me to be on a tour I'm not leading.

On the open road at 17—bitten badly by the travel bug

On the open road at 17—bitten badly by the travel bugIn September 1978, I went to Europe on business for almost a month. I was making the grand tour of the European divisions of the corporation I worked for as its public relations manager. I had been to West Germany, Holland, England and now found myself in Scotland. It was my first time in Europe, and was enthralled by its history and culture.

Scotland was special. It was enchanting. Maybe it was the incredible green of it all, the luminescent quality of the northern light or just the buoyant, down-to-earth nature of the Scots. And the introduction to Scottish central heating—single malt whisky—didn't hurt either.

Glenfinnan Viaduct, West Highland Line

Glenfinnan Viaduct, West Highland LineMy wife Linda and I returned to Scotland in 1987, this time taking in the Hebrides Islands. We intended to go again, but life intervened, In 2002, I lost my one good kidney to high blood pressure and heredity and have lived with chronic illness, end-stage renal disease, ever since. I spent the next 6 1/2 years on hemodialysis, the last three doing home hemodialysis on a NxStage machine, often traveling with it all over the United States.

I received a successful cadaver kidney transplant in 2008 at age 63. Once I was transplanted, I knew I could travel freely without the need for dialysis treatments. The gift of air mileage from a dear, longtime friend, gave us the impetus to go back to Europe. And go we did in May 2019, self-touring the UK for three weeks by rental car—over 2,100 miles from Southwest England to Wales, Northumberland, and finally Scotland. We then flew to Denmark for a week.

Linda and David Rosenbloom with Henning Sondergaard in Scottish scotch whisky country

Linda and David Rosenbloom with Henning Sondergaard in Scottish scotch whisky countryWhen I was researching and planning the trip, an activity I love to do, I automatically thought about inviting Henning to come along. We have so much in common and had grown very close over the years we've known each other advocating for kidney patients. He had always wanted to see Scotland and jumped at the chance to go with good friends. Our Scottish vacation sounded ideal, until you consider that Henning not only does his own hemodialysis but also has been confined to a wheelchair since age ten due a congenital condition, spina bifida. He is now in his early-fifties. Henning also has only one leg, having had the other amputated when he was 25 as a result of an accident. Add to that his "senior" traveling companions, my wife and myself both in our mid-70s, and you've given yourself a big challenge.

HenningTravel is one of the most broadening experiences one can have. It opens one's vistas to new people, new customs and hopefully new horizons. I learned the joys of traveling from an early age. I was fortunate enough to be able to go to other countries without my parents from the time I was 14 years old. I would go to sporting events all over Europe. It opened my mind and my heart to how different life can be lived around the world. One could say I didn’t learn to travel despite my disability but because of it. I got to see how others coped with their impairments. This was very inspiring for a young man whose self-esteem was not yet particularly well developed.

Me at 15 with some of the guys from my basketball team

Me at 15 with some of the guys from my basketball teamI have always had a strained attitude towards the wheelchair being the symbol of disability in general. Yes, it is very recognizable, and no I never have to explain why I am disabled–—I am the embodiment of the symbol for disability. So, while a wheelchair is seen as an inconvenience to most other people, I see it as a symbol of my freedom. From the time I was ten years old, my wheelchair was a means for me to get around. Granted, I could walk with crutches until I was in my early twenties, but the chair was always my preferred mode of transportation. It was my legs and my bicycle at the same time. I had mastered the chair to such a degree I was on the national wheelchair basketball team when I was 15 and the second person in my country to finish a marathon. By the age of 17, travel had become an integral part of my life.

I jumped at the chance to go to Scotland with David and Linda. I have always wanted to see Scotland having heard so much about its beauty and the friendliness of its people, its wild history—and Scotch whisky, of course. I knew we would have to look for a large van, wheelchair accommodations, etc. But that did not faze me or David. We rolled up our sleeves, got on the Internet and found the resources we needed at prices we could afford. We all wanted to experience small town, rural Scotland. In big cities like Glasgow and Edinburgh, I knew it would be easy to get around in my chair. But we already live in large cities with millions of people and crowded museums and nice restaurants. David wanted me to see the Scotland he loved and had been to before. And that was the country I was most interested in as well.

Traveling with my dialysis machine and supplies requires a good deal of pre-planning. But it is not necessarily a big burden. And the joy I gain from going places far outweighs the inconvenience of carrying medical equipment. It has become part of my life, like my wheelchair did when I was 10 years old. Wherever I go, my machine follows. Whether it’s within driving distance where I have a van with hand controls and a ramp or it’s trips where I have to travel by plane doesn’t matter, I bring the things that are necessary for me to sustain my life.

I was a child when I had to adapt to living in a wheelchair. So I did. I had no choice. But to me, adapting also meant breaking pre-conceived boundaries. I have done things people would think undoable in a wheelchair. So traveling with the restriction of lugging my NxStage machine with me is just an extension of the life I have always lived. Of course, I have gotten older and wiser. I like way more comfort than I did when I was young and stayed in the sauna house at the Nordic Ski Center in Breckenridge, Colorado for four days before I found decent accommodations. But the attitude of doing whatever I put my mind to is still the same.

Me on a ski hill in Colorado

Me on a ski hill in Colorado

Comments

Allon Schoener

May 30, 2020 12:16 AM