The Insignificance in The Significant

When I started dialysis in the year 2000, the last thing I thought I would be doing is writing this blog 20 years later. My life reminds me of a story I read, called, The Things They Carried. I’ve come to think that dialysis patients are like the soldiers in that story. See, the things they carried in their utility kits described them. The contents told us of the lives they led, and the things that kept them alive and going during war.

We, the patients with CKD (chronic kidney disease), and ESRD (end-stage renal disease), learn about each other, out of habit, with every visit to in-center treatments. Sometimes we only learned what we know about each other through families or caregivers: the kind and caring home attendant sitting in the waiting room, the spouse who came to pick someone up, or the sibling who brought a snack or lunch. Unfortunately, some of our fellow soldiers are speechless, by choice, or condition.

We are akin to soldiers fighting in a war—some choosing quiet safety, others jovial denial, or pensive waiting; the enemy is unseen, but present. It is a battle for survival day by day. We learned what our comrades loved by observation. We saw what they like to eat, if you sat close to them, also what they like to do in their free time by conversation, saw what they watched on television, or heard the music they listened to and enjoyed.

We are akin to soldiers fighting in a war—some choosing quiet safety, others jovial denial, or pensive waiting; the enemy is unseen, but present. It is a battle for survival day by day. We learned what our comrades loved by observation. We saw what they like to eat, if you sat close to them, also what they like to do in their free time by conversation, saw what they watched on television, or heard the music they listened to and enjoyed.

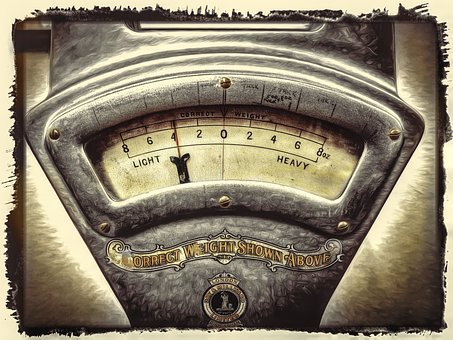

The medical communities know us, however by association of numbers: medical record numbers, k/tV —clearance, blood pressure, A1c, potassium levels, etc., and of course our old adversary: dry weight in (kg) kilograms. If you are anything like me, before you unwillingly joined the kidney disease battle, you probably didn’t even know there was such a thing as “dry weight”—those pounds absent the buildup of fluids in our bodies, which cannot be expelled through normal means. Most of us came into this battle a few pounds over what we are now, but just like soldiers on a strict ration diet, we too are on dietary restrictions to last through the battle. One example, the limited water, “32 ounces a day”—the last thing you want to do is run out of your rations before the 24 hours are over on a long hot summer day, or eat that salty snack or banana you’re craving that will affect your potassium level, and the crucial role it plays on your heart functioning properly. I’m speaking from experience. I wasn’t always a role model for kidney health.

The medical communities know us, however by association of numbers: medical record numbers, k/tV —clearance, blood pressure, A1c, potassium levels, etc., and of course our old adversary: dry weight in (kg) kilograms. If you are anything like me, before you unwillingly joined the kidney disease battle, you probably didn’t even know there was such a thing as “dry weight”—those pounds absent the buildup of fluids in our bodies, which cannot be expelled through normal means. Most of us came into this battle a few pounds over what we are now, but just like soldiers on a strict ration diet, we too are on dietary restrictions to last through the battle. One example, the limited water, “32 ounces a day”—the last thing you want to do is run out of your rations before the 24 hours are over on a long hot summer day, or eat that salty snack or banana you’re craving that will affect your potassium level, and the crucial role it plays on your heart functioning properly. I’m speaking from experience. I wasn’t always a role model for kidney health.

As an advocate for kidney disease, I fought the good fight. I’ve experienced it all: swelling, high and uncontrollable blood pressure, triple by-pass open heart surgery, potassium build up, transfusions, sepsis, you name it, I probably had it and fought through it. I am a Renal Warrior. You are a Renal Warrior, your Purple Heart is not pinned to your lapel, it is part of your organs and it’s beautiful. However, what were we before? Before the dreaded day we found out we had a connection to each other’s lives, by extension of oversized needles piercing skin, and blood tubes connected to humming machines, that clean toxins out of our bodies? What were we before the medicines we collectively consume, and the diets we share - inevitably determining our life span? We were simply: children, mothers, fathers, siblings, and grandparents, even caregivers. Moreover, as of today our lives are not much different than anyone else’s. The battle they fight, the cross they carry is just different. Nobody promised anyone a forever-rose garden, and no one can predict the unknown mortality of it—the flowers we smell in the midst of the turmoil we walk through; the storms we face.

But we stay hopeful, like a soldier trudging muddy roads, through thick jungles filled with insects, and venomous snakes; deadly predators are all around us. The creatures we are on the lookout for, and have to sharpen our senses for, are tangible, but unseen to the human eye. A microscopic enemy on the attack has now inhabited our lives, telling us what we can do and when we can do it, to stay safe— wear a mask, take your meds, sterility and aseptic at all cost.

Our immune system is the only warfare ammunition we wield, and it is gentle and fragile. Sometimes we feel like we are pushing a boulder uphill, all by ourselves, with a medical care team cheering us on from the bottom on the way up, and our families standing by the finish line on the top side, hoping for our victory. With swollen limbs, pinpricked extremities, bulging bellies, and stressed heart muscles, we traverse the world of modern medicine, thirsty, looking for a cure to the yet un-curable, knowing that we cannot give up.

Always pushing the boulder in front of us, carrying our utility kit on our backs: the oversized bags we carry with blankets, to protect us from the cold chill of a sterile dialysis room floor, the blood pressure pills, and phosphorous binders, and Benadryl that stop the itch—encompassing itch, much worse than the singular mosquito bite one gets in green lush jungles.

In our knapsacks are the hard candies, to prevent us from getting thirsty, and that favorite book to help our mind escape the clean, sterile, antiseptic rooms of dialysis nurses, doctors, technicians, or perhaps headphones to drown out the hum of that infernal machine, and go to lands of joy, intellect, mystery, or reality; for just 3 to 4 hours a day you are there—three times a week—in a controlled atmosphere, depending on others to keep you safe and alive. My survival book is my Bible; my faith sustains me. We all have that something: a picture of a love one, that unfinished manuscript, that businesses plan, or that positive affirmation that keeps you going.

There is joy in hope, and sometimes an ounce will do. After being on dialysis for eleven years, receiving a kidney transplant in February of 2011, only then, did I noticed the knapsack I was carrying around all those years before. It was full of determination, missions, compassion, to-do list, ambition, and at the bottom, the insignificant shame, embarrassment, and disappointment. I was locked into an ever-growing community of systematic life-giving procedures, while carrying around the fears of my teenage boys, who had already lost a father to tragedy. I hauled around the concern of two older sisters, who would inevitably take on the enormous responsibility of being guardians. The heaviest was the worry of an aged voiceless mother from a stroke, with the look of compassion, and sadness in her eyes, that she tried to hide with a beautiful smile. It brightened my days, letting me know that in her 90 years she had endured and won many battles. She was always there for me. As she was in life, she is now incorporeally in death. Her words of wisdom, her strength through adversity, her gentile humility, and her humor is with me in memory.

There is joy in hope, and sometimes an ounce will do. After being on dialysis for eleven years, receiving a kidney transplant in February of 2011, only then, did I noticed the knapsack I was carrying around all those years before. It was full of determination, missions, compassion, to-do list, ambition, and at the bottom, the insignificant shame, embarrassment, and disappointment. I was locked into an ever-growing community of systematic life-giving procedures, while carrying around the fears of my teenage boys, who had already lost a father to tragedy. I hauled around the concern of two older sisters, who would inevitably take on the enormous responsibility of being guardians. The heaviest was the worry of an aged voiceless mother from a stroke, with the look of compassion, and sadness in her eyes, that she tried to hide with a beautiful smile. It brightened my days, letting me know that in her 90 years she had endured and won many battles. She was always there for me. As she was in life, she is now incorporeally in death. Her words of wisdom, her strength through adversity, her gentile humility, and her humor is with me in memory.

The challenges of in-center treatments often seemed insurmountable: getting stuck in snowstorms, braving long hospital stays, fighting infections, doing dialysis whether sick or well, but it was mostly the loss of independence that hurt the most. My proverbial knapsack held the tangible: gauzes, tape, and bandages, the needle pierced skin, the blood we shed—dried on flesh and clothes, the cellphones we have on hand in case of emergency to call friend or family, and let them know we are on our way to the hospital (because of unforeseen circumstances), clinic cards, emergency alert bracelet, insurance cards, doctors and nephrologist names, telephone numbers of, emergency contacts, and my Bible. My utility kit, just like the soldiers told who I was, no dog tag necessary.

In contrast, the day of my transplant was one of the best days in my life, besides the birth of my children, now young men. I had a new emergence of life, but this time with liberties. But don’t get me wrong; I still had that invisible, heavy, all-consuming bag on my back. The contents in it were intangible, telling the story of my life, who I was, the time I lost, who I could have been, my aspirations, my dreams, and all I could do with this new opportunity, without physical constraints.

There were: quiet tears—mourning a life that once was waking dreams of what I would and should have become; the incorporeal, at the top, the love experienced with indelible enchantment. Somewhere in the middle—the darkest part, distant sounds of laughter—from family no longer alive to encourage me to push on; at the very bottom of the bag, the look on a close friend’s face, who I never got a chance to say goodbye to as EMS rolled them out the last day I saw them at dialysis.

I’d never thought I would be here, again, my life attached to the inconvenient conveniences of my portable hemodialysis machine. It sits here besides me now, in my makeshift medical room, making that quiet comforting hum I’ve grown accustomed to. For 7 years I lived free: went back to college, earned my degree, started a Grass Roots organization, published poems, wrote, and produced a play, started a theater production company. I accomplished a few things; I was giving back. I am grateful, and encourage you to go for yours, get on the transplant list, do the work, comply, comply, comply. For those who choose not to, I understand. This journey is personal and real.

Although my transplanted kidneys failed again, I would not turn the clock back for all the gold in the world. Because I found the freedom of home hemodialysis, as I continue to roll that boulder uphill again, knowing eventually I will get to the top of the mountain. I’m learning the hard knock lessons—catalyst for the new blue ribbon life I live. I recognize the insignificance in my significant life. I recognize that those band aids, gauzes, triple antibiotic, chucks, tape, etc., are nothing without me, without those 5 weeks of training, without my home hemo nurse, my doctor, or the person who suggested I could handle doing and being, technician, patient, and inventory clerk. Nobody can cares more about me than me, other than God. I chose doing dialysis at home for the freedom, flexibility, and convenience with a small cost called responsibility. I carry my utility kit proudly, and all the scars that come from the war against kidney disease. It’s one of necessity; lets carry ours proudly, caregiver or patient, indiscreetly, humbly every day on the battlefield. And to all you warriors, one day, together we will defeat this enemy called kidney disease. We can win this war.

We carry the hopes, dreams, worries, and concerns of our family, friends, and if we are lucky enough the medical support of doctors, nurses, dieticians, and social workers.

As home hemo, or peritoneal dialysis patients, we carry with us the heaviness of many obstacles: physical, emotional, mechanical, technological, and worldly. As one HHD patient put it, “no one could understand or comprehend the complexities, and traumas we experience, unless they experience them..” However we have dreams, hopes, and lifestyles, and I hope those reading this get a glimpse into the pros, and cons of our choices in the fate of chronic kidney disease.

Comments

Kalispell Gazette

May 08, 2021 7:15 PM

Sue

Mar 02, 2021 10:43 PM

Your blog “the insignificance in the significant” was published in the latest Kidney society news(New Zealand)

Wow! A beautifully written blog that touched my heart. I love the way you have likened those going through life with dialysis/transplants to soldiers. You have empowered them all that read your article. How wonderful.

You write beautifully. My husband has been a renal transplant patient for 35 years having had dialysis and three transplants! I have lived and breathed it too and you have captured it in such an inspiring way.

Thank you so much.

Please know that your message is being received in New Zealand and being read as we speak.

I wish you all the best in your life.

Sue

Leong Seng Chen

Jan 08, 2021 12:43 AM

I am with AV Graft for 6 years plus engaging in haemodialysis (HD) treatment at NKF SIngapore. I am 74 years old now & find my life-journey is satisfactory too! Your story is truly touching & moving me to keep on moving on along my life-journey!

Thank you once again & HAPPY 2021 NEW YEAR!

Yvonne Coleman

Jan 08, 2021 6:00 AM