The Power Of Curiosity In Shared Decision-Making

“The most important part of a story is the piece of it you don't know.”

― Barbara Kingsolver, The Lacuna

Nephrology health care providers balance the competing demands of time, financial incentives, and the inherent expectations of their roles with the individual needs of people living with chronic (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Algorithmic processes—like annual care plan meetings—have evolved as strategies to manage the demands of the ESKD professional. Algorithms, by design, provide structure and certainty about a response to clinically ambiguous and time-sensitive situations. A potential risk of an “if this, then that” approach is losing the patient focus and nuance in understanding that is necessary for modality decisions.

The ambitious goals of Executive Order 13879, Advancing American Kidney Health, to have 80% of new end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients receiving home dialysis or a transplant by 2025, has presented providers with an opportunity to shift to a more patient and family-centered, values-based SDM process. The impact of dialysis decisions has profound interpersonal and societal implications as dialysis patients account for 1% of the U.S. Medicare population and 7% of the Medicare budget.1 Additionally, through the 20-25 hours a week of task assistance with daily living and medical management activities, informal caregivers (e.g., partners and adult children) are a vital part of the healthcare workforce with an economic burden of $234 billion.2,3

Shared Decision-Making and Patient-Centered Care

Nephrology care teams balance incentivized demands to promote home dialysis with the realities of patients and their families' lives. Shared decision-making (SDM) is considered the gold standard practice in dialysis treatment decision-making.4 Health care providers that engage in SDM ensure patients are informed about and included in the health care decisions. SDM is more than an information delivery model. It is a relational process that aims to help patients, their families, and their healthcare providers consider choices, information needs, values, and preferences. The health care professionals, patient, and family share responsibility for the final treatment decision. Each party may not agree with the decision, but each party agrees with the plan.

Rather than recognizing treatment decisions as a relational process that develops over time, decisions are often understood as episodic choices of access placement, treatment modality, and advanced care planning. Approaching dialysis modality discussions as an algorithm rather than a relational SDM process has far-reaching implications for patients and their decision partners. Failing to use an SDM approach that includes patients and decision partners may lead patients to feel as if they have limited choice about their treatment options.5,6 Once a patient starts dialysis, these decisions often occur within the context of care plan meetings.

Rather than recognizing treatment decisions as a relational process that develops over time, decisions are often understood as episodic choices of access placement, treatment modality, and advanced care planning. Approaching dialysis modality discussions as an algorithm rather than a relational SDM process has far-reaching implications for patients and their decision partners. Failing to use an SDM approach that includes patients and decision partners may lead patients to feel as if they have limited choice about their treatment options.5,6 Once a patient starts dialysis, these decisions often occur within the context of care plan meetings.

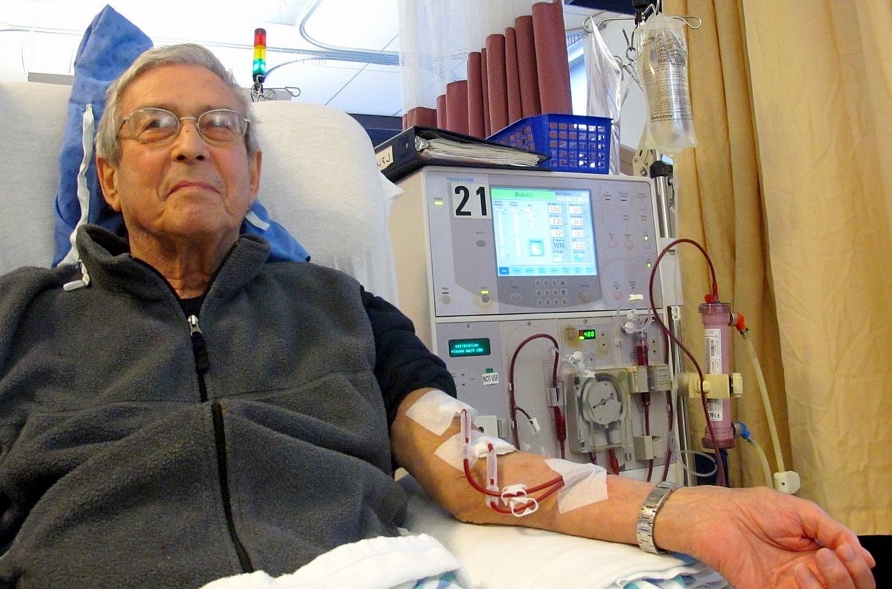

The values, beliefs, and feelings toward life, suffering, death, and expected difficulties of fitting dialysis into daily activities are considerations of people making modality decisions. Despite evidence that patients and their decision partners have values and preferences better matched with home dialysis modalities, 89% of patients start standard, thrice-weekly in-center hemodialysis (ICHD).7 Compared to home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, ICHD has higher rates of depression, side effects like fatigue, infection, hospitalization, sudden cardiac death, and lower survival. Further, ICHD interferes more than home treatments with work, social roles, and other activities consistent with patient values and goals.

The values, beliefs, and feelings toward life, suffering, death, and expected difficulties of fitting dialysis into daily activities are considerations of people making modality decisions. Despite evidence that patients and their decision partners have values and preferences better matched with home dialysis modalities, 89% of patients start standard, thrice-weekly in-center hemodialysis (ICHD).7 Compared to home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, ICHD has higher rates of depression, side effects like fatigue, infection, hospitalization, sudden cardiac death, and lower survival. Further, ICHD interferes more than home treatments with work, social roles, and other activities consistent with patient values and goals.

Additionally, disparities remain in the use of SDM with African American patients. From 2002-2013 Black/African American patients reported less adequate communication with healthcare professionals (HCPs )than their white counterparts.8 African American patients are less likely than white patients to have HCPs consult with them regarding treatment decisions, are less likely to ask questions during visits, and receive less treatment-related information. Physicians are less likely to discuss their experiences using a treatment or to share scientific research about treatment efficacy with minority patients.9 These communication disparities are problematic, as patients of different races and ethnicities value different attributes of treatment.10 African American patients with diabetes identified information sharing, and “feeling heard” as the most important domain of SDM.11 African American patients reported they were less likely to participate in SDM with HCPs who impeded trust development by not listening to their stories.

Curiosity May Be the Missing Piece

While education is essential, knowledge in and of itself is not enough for patients to make fully informed treatment decisions. An SDM interaction that starts with curiosity between patients, decision partners, and providers may help patients to better understand their diagnosis and treatment options, increase satisfaction, and increase involvement in care.

Patients and health care providers are contextual—set within social, cultural, and personal histories that influence their values, beliefs, and practices. The psychological, financial, legal, scientific, educational, and spiritual context of the patient and health care provider influences how treatment decisions are presented and considered. Provider bias shaped by context and a desire to promote a patient’s best interest influences the patient interpretation of choice.12

Curiosity through questions can allow health care providers to take a position of empathy (standing as if in someone’s shoes) with a back and forth, ask and answer conversation between multiple partners that allows for the modifying and replacing of preexisting concepts. Rather than a chronological, objective, and algorithmic dialogue of diagnostic conversations, the provider and patient can mutually engage in offering up understandings for confirmation, modification, or rejection to understand experience, motivations, needs, and conditions.13

Moving from a position of convincing a patient and family towards a curiosity perspective can help patients, their decision partners, and the health care team understand why a family holds a particular view. Decision aids can be used to prepare patients for the discussion with the treatment team to supplement—rather than replace—a relational SDM process. The first values-based dialysis decision aid, My Life, My Dialysis Choice, can help patients, decision partners, and the health care team explore, clarify, and weigh goals and options, increase health literacy, and prepare patients for SDM.14 This process, in which a patient and decision partner explore likely outcomes and HCPs explore the values and general approach to life of the patient system, facilitates patient autonomy by better understanding what is relevant to each stakeholder. Rather than the chronological, objective, and algorithmic dialogue of annual care plan meetings, curiosity can help providers, patients, and decision partners explore the potential impacts of dialysis modality on the patient.

Health care providers who are lucky enough to care for people living with chronic disease have the opportunity to build relationships over time. Time allows nephrology care teams, the person on dialysis, their decision partners, complex, deep, and meaningful relationships. Approaching these relationships with curiosity facilitates connection—enabling meaningful conversation in modality decisions.

Comments

Mary Beth Callahan, ACSW/LCSW

May 29, 2021 7:54 PM

Renata Sledge

May 12, 2021 8:05 PM

Melville Hodge

May 07, 2021 1:37 AM

Unfortunately, I believe it is irrational to expect a patient with the symptoms of stage 5 chronic kidney disease (or their partner) to carefully weigh what is too often presented as a lifestyle decision when for many it will become a life and death decision. Moreover, the primary information source for that decision, their nephrologist, is too often biased by lack of training and experience with home dialysis reflected in the stubbornly low choice of home dialysis by their patients. The literature documents that nearly all nephrologists would choose home care for themselves! This suggests that nearly all understand the benefits, but most are not prepared... or perhaps willing... to take on the management of home care patients.

In my view the compelling arguments you cite are sufficient that the common goal should be to make home dialysis the default option... and in-center dialysis reserved for patients where home dialysis must ruled out based on significant patient-specific factors important enough and sufficiently documented to justify accepting the prospective negative clinical consequences.