An Anemia Saga

Many of you know that anemia management is one of my passions. Delivering quality patient centered care in kidney disease and dialysis includes comprehensive anemia management. Yet, I notice many people asking questions about managing their anemia and suffering from deficient lab values. In addition, I just experienced a severe bout of uncontrolled anemia, and so I feel compelled to revisit the issue and comment.

Background

Background

Early in 1990—long before CKD became an issue for me—I suddenly suffered from severe, adult-onset asthma attacks. They almost appeared cyclical in nature. During the following years I was treated by doctors, pulmonologists, even cardiologists, but no one could get the “asthma” under control. When these attacks struck, I felt like I was drowning. I was gasping for air that I could never seem to get enough of. None of the standard asthma treatments worked. Many of those treatments actually contributed to the onset of CKD by causing acute kidney injury (AKI).

Fast forward 25 years to a lung procedure called bronchial thermoplasty, a final effort to try to control the inflammation in my lungs that caused these severe attacks. This time I crashed right into dialysis. During the procedure I became physically distressed. When I came to, there was a nephrologist standing by my bedside, telling me it was time for dialysis.

Fortunately, this nephrologist, unlike the previous three, insisted that I do home dialysis. In 20 years, no one had ever mentioned a home option. I was convinced I would not last a day doing incenter dialysis, but a home option? Long story short, I went home to train for home dialysis once my fistula matured. That first year passed by in a blur. The only thing I did notice was that I had no more breathing issues. I found that strange.

Over time, I began to learn both about my home dialysis AND about dialysis in general.

I began to understand my labs, what they meant and what I was being treated for. This is when I started learning about anemia.

I knew I had been anemic since the 80's. Doctors just treated it nonchalantly, summing it up as a disease for ladies who were “fat and 40.” I never knew otherwise, until I started dialysis. I began to understand what happened when my hemoglobin dropped, what my TSAT was, and where my iron and ferritin levels were—and more importantly, I learned how I felt at various times with different lab values.

Fact: Anemia increases the rate of deterioration of renal function in patients with CKD and therefore the rate of progression of renal failure to dialysis.1

Until recently one thing remained constant. As long as they were treating my anemia, I no longer had the debilitating “asthma” attacks. But, for the last year or so it has been harder to control the fluctuations in my hemoglobin levels, along with high ferritin levels and low TSATs. I call this the EPO yo-yo. By the time I would get my monthly lab results, my hemoglobin had dropped to around 10, from my normal of 11.5. My clinicians would initiate EPO dosing, and occasionally iron, and wait to get results from labs a month later. I have repeatedly experienced this EPO yo-yo: low hemoglobin, increase EPO ‘til it reaches 11+, withhold EPO, hemoglobin drops, and the cycle continues.

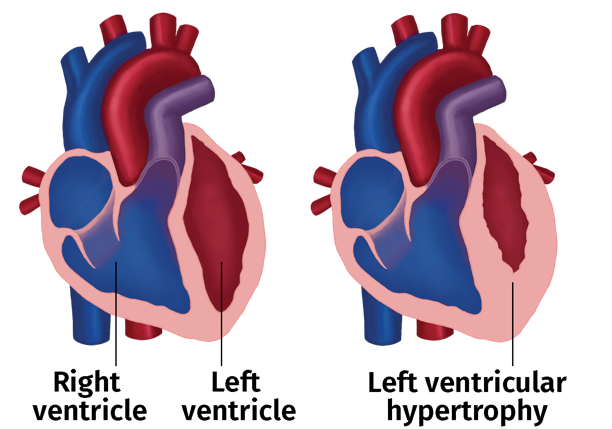

Medically, this is a vicious cycle: congestive heart failure (CHF) causes anemia, anemia causes more CHF, and both damage the kidneys—and further worsen the anemia and CHF.2 The anemia can reduce cardiac function, both because it causes cardiac stress through tachycardia and increased stroke volume and because it can a restrict renal blood flow and increase fluid retention, adding further stress to the heart.

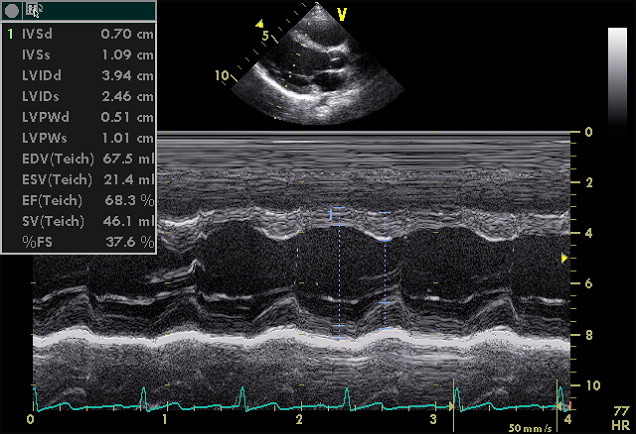

Longstanding anemia of any cause can cause left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), which worsens the CHF. In my experience, this is a phenomenon rarely understood by any clinician. In laymen's terms, due to the low iron (iron is the “heme” of hemoglobin, which carries oxygen), organs do not receive the proper nourishment, i.e. oxygenated blood, often despite a pulse ox of 97. This puts severe stress on the heart, lungs, and kidneys. What had appeared as my uncontrolled asthma was actually shortness of breath triggered by anemia. Who knew?

I am very fortunate that my nephrologist and clinic nurse understand how debilitating my anemia is and work with me to effectively manage it. For example, instead of withholding EPO when my hemoglobin is in the 11 range, we cut the dosage to as low as 500 units. Additionally, since I am prone to iron overload, following the clinic protocols of venofer doses of 100-200 units weekly is contraindicated. Instead, when my TSAT drops, we initiate a low dose of venofer (50 units) weekly or every 2 weeks, until the TSAT is within normal limits. This seems to have worked well over the last few years.

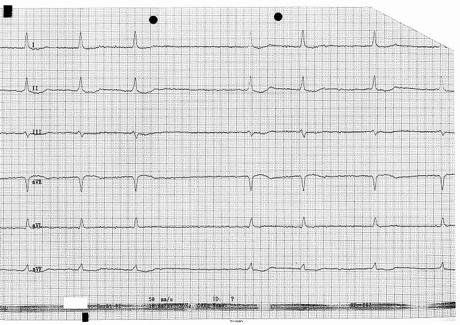

However, recently I experienced a severe decrease in all of my iron function labs, including TSAT and hemoglobin. For some reason, possibly an underlying inflammatory response, I was very slow to respond to increasing doses of EPO and iron. In short, it took almost 2 months from first becoming aware of my low anemia levels to respond to treatment. The stress on my heart during this time ultimately triggered Afib.

Now, this is where the story gets interesting. In anemic patients with CHF, correction of anemia with EPO and oral iron should lead to improvement in heart status, measured exercise endurance, oxygen use during exercise, renal function and plasma B-type natriuretic peptide levels and reduce the need for hospitalization.

Try telling that to anyone besides your nephrologist. My Afib was discovered during a routine checkup at the hematologist, of all places. He sent me directly to the ER. The minute I mentioned anemia, they all looked at me like I was certifiable. And when I said my TSAT had been at 12% for more than a month, causing the stress on my heart, the response from every cardiologist, hematologist, and hospitalist was “What's a TSAT?”

When I told my hematologist that the Afib was triggered by the uncontrolled anemia, he literally accused me of “shooting up” venofer and inducing iron overload. The cardiologist's response was, “Well, you are not anemic NOW! You have Afib,” and then even more condescendingly, “Do you know what Afib IS?”

In any case, let there be no doubt that BECAUSE I was so slow to respond to increasing doses of EPO and venofer, my anemia was essentially uncontrolled for several months. In this particular instance, my heart was damaged, which triggered the Afib. I know this because I had checked my heart function with yearly echocardiograms monitoring LVH and ejection fraction, and any other potential heart issues. Mine were all fairly normal for someone approaching 70 and on dialysis for 9 years—until this recent bout of uncontrolled anemia placed considerable stress on my heart. There are inordinate amounts of studies that support this diagnosis, called cardiorenal anemia syndrome (CRAS).1

This interaction between chronic heart failure, chronic kidney insufficiency and anemia, form a vicious cycle, CRAS, causes deterioration of cardiac and renal function and increases the anemia. Each of the three can caused or triggered by the others.

Congestive heart failure (CHF) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) often progress to end stages even with optimal medical therapy. One factor that is common to both these conditions is anemia, which is present in about a third of CHF patients. CHF can cause or worsen both anemia and CKD, and CKD can cause or worsen both anemia and CHF.3 Congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease and anemia appear to act together, with each condition causing or exacerbating the other two. Both congestive heart failure and anemia are often undertreated. Cooperation between nephrologists and other physicians in the treatment of patients with anemic congestive heart failure may improve the quality of care and the subsequent prognosis for both congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease.4

Herein lies the problem. How can our clinicians collaborate and cooperate in treating Cardio Renal Anemia Syndrome if they

Don't even know the diagnosis exists?

Don't understand or are not aware of lab tests used to diagnose the disease?

Don't communicate with each other when treating the disease?

In 1/3 to 1/2 the cases of congestive heart failure, anemia has been found to be caused not only by chronic kidney disease but by the congestive heart failure itself. The anemia is associated with worsening cardiac and renal status, often with signs of malnutrition. Control of the anemia and aggressive use of the recommended medication for congestive heart failure may improve the cardiac function, patient function and exercise capacity, stabilize the renal function, reduce hospitalization and improve quality of life.

Over the years, as I have learned about the kidney-anemia connection, I have suspected that if I had received treatment for the anemia early in my CKD diagnosis, I might never have crashed into dialysis. This last crash was exactly the same as the initial crash that started my dialysis journey, but with the addition of Afib. Yet during the 9 years of dialysis when my anemia was treated aggressively, I experienced no more “crashes.” I am not sure we will ever understand what caused this recent bout of severe anemia, but one thing is certain: I am not sure I can survive another one.

The good news is that, after seeing a handful of cardiologists, one of them finally prescribed the correct medications, including a cardioversion intervention to reverse the Afib. I am happy to report that they worked, and my health has improved considerably. In consultation with my nephrology clinicians, I am doing weekly anemia labs at my local hospital to closely monitor my anemia levels and correct any deficiencies immediately. Hopefully this effort will help to avoid future anemia “crashes.”

I want to leave you with some concluding thoughts. Anemia kills. It is that simple. Untreated and undertreated anemia, as I hope you have learned here, often cause a vicious cycle of cardiac, renal and anemia disease. Left untreated, any one of them can contribute to mortality. The fact that they are so intertwined in a “Which came first? The chicken or the egg?” scenario should be a warning to clinicians and patients alike. Do not ignore the symptoms of anemia.

But that is exactly what I see happening, especially in light of the recent trend for clinics to switch from the long-standing treatment of epogen to Mircera or Aranesp (monthly injections) to manage anemia. People are posting:

“Low hemoglobin was one of my hubby's AFib triggers. His other AFib trigger was dehydration. I just messaged the clinic for EPO. They are wanting to switch him to Mircera once he's able to go to the clinic for the alternative med and I'm hoping they don't switch until we get it under better control!!”

“Every time they stopped the Epogen due to high hemoglobin he would drop to a low hemoglobin. Finally, I was like look, I am not doing this on again off again anymore. I'm tired of my son feeling bad every time we stop his Epogen. So now his doctor just adjusts his dose per his hemoglobin. And he feels so much better.”

“I cannot believe any clinician would say “it's better to be a little anemic.” So frustrating! How can that possibly be beneficial to a patient?”

“My clinic keeps my hemoglobin at 10 at the most and won't let me get higher. They say it's dangerous to be above that as a dialysis patient, but I'm not clear why? I get as low as 7 sometimes, and then they put me on double dose of Mircera when it is below 8.”

“EPO works much better I would say after 3 years on it alone. Then came Aranasep and now Mircera which requires the up-down dance of your Hgb.”

“EPO works for me and has for over 7 years. Nurse and doctor said my clinic is switching and we have no choice, their words. I have no issue switching if I've had issues with EPO, but I haven't.”

Great that Mircera works for you, it doesn't work for everyone, though. Neither does EPO, or Aranesp. That is why it is important to not make medical decisions based purely on money. Low Hgb causes heart damage.

In conclusion, the severity of anemia in patients with CKD is an independent predictor of death, and the risk for cardiovascular events, including stroke, is increased significantly when anemia is present5. Similarly, in ESRD patients, correction of anemia has been shown to prevent, improve or even correct left ventricular (LV) dilation and LV hypertrophy, reduced hospitalization and mortality and improved quality of life. Bottom line, anemia kills, and we, as patients, must bring awareness of this issue whenever and wherever we can.

Efstradtiadis G, Konstantinou D, Chytas I, Vergoulas G. Cardio-renal anemia syndrome. Hippokratia. 2008 Jan-Mar;12(1):11-16↩︎

Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Iaina A. The role of anemia in the progression of heart failure. Is there a place for erythropoietin and intravenous iron? J Nephrol. 2004 Nov-Dec;17(6):749-761↩︎

Iaina A, Silverberg DS, Wexler D. Therapy insight: congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease and anemia, the cardio-renal-anemia syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2005 Feb;2(2):95-100↩︎

Silverberg D, Wexler D, Blum M, Schwartz D, Iaina A. The association between congestive heart failure and chronic renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2004 Mar;13(2):163-70↩︎

Comments

Bruce Hinson

Jul 30, 2022 3:25 AM

Mohammad Faisal

Jul 15, 2022 3:01 PM

Thanks

Faisal

Nieltje Gedney

Jul 17, 2022 2:00 AM

Erich Ditschman

Jul 15, 2022 2:33 AM

Nieltje Gedney

Jul 17, 2022 1:57 AM