Safety First! How to Prevent Dangerous Home Hemodialysis Errors

If you gathered together people with intimate knowledge of home dialysis, and asked for their stories, you would surely hear a lot of really great things. We all like the good stories—of triumph, travel, and perseverance. Patients really do report a better quality of life at home. The overall mortality of home patients is lower than for patients in clinics, especially for those patients who run excellent and gentle treatments. The good stories are so abundant!

…But what about the bad stories? Are we glossing over those? Painting a pretty picture while ignoring honest and legitimate concerns?

Eventually, the not-so-great stories start getting told, too. It’s inevitable. For those of us who advocate for home dialysis, we are quick to point out that adverse occurrences are pretty rare. They are. However, critics seem to be quick to point out all of the “what-if’s” in play, and I personally feel safety concerns should always be addressed.

I follow several dialysis-related Facebook groups and have absolutely read things that were unsafe and alarming per my own standards. I have wondered about the extent of nationwide training standards due to learning deficits I’ve identified in a single post. I don’t mean to make anyone feel called out, but no clinic should ever be discharging a patient to home HD who does not know how to administer a saline bolus to themselves, for example. Not unless that clinic wants a patient to fail, or potentially die.

I have heard countless stories like this from patients that I’ve wished I could share further into the home dialysis discussion communities, because there’s good chance that knowing these anecdotes could make others safer, but hasn’t…yet.

Maybe now is a good time to start having this conversation.

For those of us that have seen, read, and overheard accounts by those who have done some home dialysis but transferred back to full-care due to a complication or preventable event, have we taken their grievances seriously? What can we do about things we know to be occurring so patients feel safer going forward? Are we adequately addressing the scary things? Are we recognizing that all humans capable of blunders, and therefore, all people require reminders?

Some of the most powerful learning takes place in the midst of errors, and we would likely be doing a much better job of educating staff and patients if we took a more honest approach in accounting for occurrences and were able to share our experiences in a more widespread manner, without fear. I wonder if there is a need for an anonymous way in which to do so…

I direct these questions to patients and staff alike to address in the comments at the end of this blog:

What some real things you have learned in dialysis by error or accident?

What are things everyone needs to be warned about so we can be safer as a community?

What preventable mistakes have you have made, or witnessed, that would serve as good teaching moments for the benefit of others?

I have a few of my very own I’d like to start the conversation with:

Verify Functionality of Blood Leak Detection Alarms

If you read the forums enough, you will inevitably come across several stories from patients that involve running treatments without blood detection alarms on the exterior of their machines and experiencing an undetected catastrophic loss of blood because of it.

A loose connection, missed heparin-line-clamp, or slow leak over a long treatment can cause a person on dialysis to lose a lot of blood very, very, quickly. Everyone should have simple battery-operated devices that can save lives by emitting a loud, annoying, ear-piercing, screech when they become wet if running hemodialysis at home. If it were up to me, patients would have no less than three of these, one for the machine, one for the chair, and one for the floor. I have admittedly been called “extra” by patients. I don’t care. I much prefer an annoyance to a tragedy. The clinic is required to provide these alarms to patients.

I have no idea how many people are currently out there running treatments without a functioning alarm, but I really wish no one would ignore this small safety precaution. Batteries die. The devices eventually wear out and the connections rust. When they do not work, they cannot save lives. Are patients really checking these packs for functionality regularly? Are clinics reenforcing this? Do patients know that they can touch a damp paper towel to their moisture sensor to make sure it works? I am not so sure.

I once decided to check my theory by surveying about 50 people on home HD and asking them to check their sensors over the phone. I found 14 who had non-operational alarms. Advise patients to check sensors and replace the batteries. If this advice saves one person from the horrifying realization that their blood is all over the floor, it is a win.

Resist Alarm Fatigue and Button-mashing

I have also heard many stories about patients ignoring or resetting alarms automatically, without doing any precautionary status checks on themselves or their systems. Alarm fatigue is a thing in clinical care, and everyone should be aware of it.

Those who are regularly exposed to the beeps and alarms of medical devices can very easily become desensitized to the sound (“tune it out”) and can fail to respond appropriately if used to repeated false-alarms. This is a dangerous way to lose control over a situation, and clinicians are warned about it. Are patients?

Even when alarms are annoying or redundant, they are built into machines to prevent potentially harmful human errors. If a machine is detecting a change or an unsafe condition, it’s reckless to not follow-up by checking the situation and ensuring that nothing is abnormal. I have witnessed several patients in the forums who had partially dislodged needles and ignored pressure alarms—not realizing that the alert was indicating blood loss. Preventing alarm-blindness and reminding others that this is critically important to be aware of is the responsible thing to do.

Whenever there is an alarm, there should be a corresponding checklist of actions to ensure safety. These things can’t be ignored without being unsafe, and complacency is very dangerous when dealing with an entire blood supply. Never forget what you are doing and why. It’s okay to go slow and be meticulous, better than the alternative for certain.

Be Mindful of Rinseback Direction

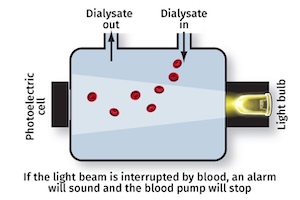

This is a story that I’ve heard personally, read in literature, and seen out there in the online world several times as well. I have a terrible suspicion it is a more common occurrence than anyone realizes or readily admits. When we return blood in dialysis, the arterial (red) patient blood supply is replaced by saline, which is pulled to the filter and then pushed back to the patient through the venous line.

It is possible (on almost all machines) to accidentally get the circuitry wrong and connect the venous (blue) bloodline to the saline source instead. If this happens and goes unchecked, blood will be directed from the patient’s access directly to the saline bag. It is exsanguination (“bleeding out”) within a closed system.

I once had it happen to a very experienced patient of mine who thankfully caught it when they began to feel dizzy and saw the saline bag full of blood and on the brink of rupture. There was no horrible outcome, as the patient knew to reinfuse everything back slowly, and call for help immediately, but there have been documented deaths from this.

If more people were aware of how easily this type careless error can be fatal, perhaps the excitement of treatment being completed would lead to a less-rushed return, a more careful disconnection of bloodlines, and a life saved. One can hope we are showing patients, in training, exactly how this error can occur so that it is prevented.

Keep Blankets and Absorbent Surfaces Away from an Access

Every person who has ever worked in dialysis has likely been warned of the dangers of allowing an access to be covered during treatments. Blood leaks happen completely non-dramatically most of the time and that is what is terrifying—how silently and peacefully they can occur.

Patients in centers dialyze on non-porous chairs. I have personally seen a slow leak from an arm roll under and behind a patient’s arm in such a chair and go unnoticed for a long time even without blankets, and even with tons of excellent staff present. It can take quite a while for blood to roll down to the floor and be noticed. We think of “bleeds” as big dramatic arterial events. They aren’t always. Sometimes it’s a drop at a time, very slowly.

At home, the chances of a blood leak from a needle going unnoticed exist, especially without the constant pressure from technicians and nurses in the clinics to not cover-up an access. Patients and their partners have to be keen on self-policing for safety on this one. Patients are generally pretty chronically cold from anemia and illness. It’s easy to understand the temptation. It's also easy to understand how a fatal bleed can occur into a blanket or mattress without anyone noticing a single drop of blood fall. Towels and absorbent surfaces can make an already difficult thing to identify, impossible.

Are we showing patients in training how much fluid a blanket can hold? Are we explaining in terms of blood-pump-speed how quickly it could happen? Are we giving reminders frequently to reduce complacency? We owe it to patients to be doing this. The whole community needs to be able to see the danger and prevent it. One patient loss at home could jeopardize the autonomy of thousands.

Avoid Careless Errors

A nurse told me a lively story once at a conference about an elderly couple who had gotten themselves into a very embarrassing situation. As some of us might know, a lot of men on dialysis struggle with erectile dysfunction but many have also noticed that obtaining a natural erection is sometimes more possible during dialysis. The story I was told was that this couple, decided to take advantage of the opportunity and tried to have intercourse in the middle of treatment.

Somehow, the female partner’s leg ended up tangled up in the male partner’s venous blood line. The needle remained, but the connection between the needle and lines came undone. Blood sprayed the room like a fire-hose for a split second, and then the line fell to the bed. This was noticed instantaneously and the blood pump immediately stopped itself. Some precious blood was lost, the system was lost, and the sterility of the needle-end was questionable at absolute best.

Even though the patient survived this event relatively unscathed, with only a funny story to tell the grandkids, it’s very important to remind people that vigorous activity (God bless them, truly) really ought to be avoided during treatment to prevent line separation or needle dislodgement or blood pressure drops! This story is a really good example of why this advice is given. It isn’t actually funny, it would be if it were not also very dangerous.

I’d love to hear the stories and situations others out there have experienced that are scary, but would make home dialysis safer. Please comment below, anonymously! With time and skill can come complacency. I used to ask patients of mine to tell on themselves when they made mistakes so that I could communicate the lessons to other patients of mine for the sake of safety. Stories are how a lot of people learn best. If we can understand the bad stories more completely, hopefully we can make the good stories more frequent, and keep people happy and safe at home longer.

Comments

Henning Søndergaard

May 27, 2023 10:51 PM

The other side of this is that we as home users are aware to a degree that no nurse or tech will ever be. We know deep down (or at least we ought to) that our lives depend on doing things properly and with care. Even though it shouldn’t, it makes a world of a difference which end of the needle you are at. Being in charge of your own treatment comes with a responsibility you just don’t see with even the most diligent professional or care partner for that matter – I am sorry to say this, but it is my observation over the last 13 years when I have dealt with dialysis issues, not just my own but by talking to and helping 100s of others in the same situation. When I read thru the different things that were brought up, I constantly thought to myself “Yes, this is true – in the clinic.” I talk to loads of fellow patients and while I hear these sorts of stories, they are extremely rare in the home population and many of the examples in the blog I have never encountered from home patients while I have heard about all of them, and a whole bunch more, in clinics around the world.

I will leave a few comments on particular details. 1: Keeping blankets away from the access is a typical nurse thing to say. Yes, blood leaks into an absorbent surface are silent. But no matter how absorbent a material is, I have always felt the moisture on my arm immediately. Besides, once the blanket get wet it also very quickly gets a lot heavier. I will say you have to be more or less paralyzed in the arm not to feel something is wrong way before the leak hits danger levels – or the floor for that matter. And when it comes to noticing blood drops fall, that is how clinicians discover leaks, we use the sense of touch to detect it. And in my experience, that sense is heightened with most patients who have fistulas. I have been half – if not fully – asleep and been woken by a tiny little droplet trickle down my arm on several occasions. With or without a blanket or a shirt or whatever over it.

I have never read or heard anything about ‘alarm fatigue’ amongst home patients. I doubt it’s a thing. All the patients I ever talk to alarms are an issue of a totally different, some would say opposite, nature. Alarms are the most annoying sounds in the world. We’ll do anything to make it go away. Again, I think fatigue is much more of a clinician’s issue than a home patient’s one. I have seen plenty of clinicians who are World Champs ignoring alarms. But when the alarm is about you, you just want to make it go away. I have known patients in my unit who have felt the need to throw things across the room because the nurses ignored alarms on their machines for too long. I once was in the clinic to get my labs done and this alarm had gone on for quite a while, totally ignored by staff who were not so busy they couldn’t have done something about it. The patient had rung one of these front desk bells at least thrice and finally he threw it across the room, after grazing my cheek it landed at the desk of the nurse who claimed she hadn’t heard the alarm that had gone on for 5 minutes. Another case of ‘not my circus, not my monkeys.’ But for us it is our circus. We are the monkeys! That’s the difference!

On the other hand, you have a point when talking about people either not checking the reason for an alarm or doing something to rectify it. That is a true danger that needs to be addressed – but again, proper training and making sure people know their lives depends on it are the two key issues.

And finally, one thing I have spent years arguing for is re-training. Let all home patients come into the clinic, maybe every 2 years. Make it an event so we can meet other patients we know and maybe don’t speak to that often. Let everyone do their treatment while being observed so they don’t fall back into lazy routines. Some patients actually also find smart workarounds with little things they can teach clinicians and fellow patients. And while we are there, train all the emergency situations; have the patient show how (s)he would react in case of this, that or the other and see if they are capable of dealing with emergencies before correcting their errors. That way everyone can feel way more safe and happy to get the best treatment available.

This may have seemed like a bashing. It is not intended so. I just think we need to be smarter about what most important issues are and how to address them? Which ones belong in the clinic setting and which ones are applicable to home? Which ones are a concern for clinicians and which ones are a concern for home patients? Who worries about what? And why? And how can we learn from each other’s concerns and perspectives?

Let me end with my most horrific HHD story that had a great impact on a number of people for years. 15-20 years ago an experienced home patient bled out in his bed at home. He had a venous disconnect and lost virtually all his blood before anyone found him. This lead to his clinic putting all HHD treatments on hold from that day on. So for more than a decade there were no HHD patients in that clinic. But if someone had bothered to ask people knowing this guy, they would have learned that it was a deliberate bleed out. He had planned it carefully. He simply didn't want to live any longer. But the clinicians took it as a tragic accident that needed to be prevented, thereby denying a vast quantity of patients the best treatment available - simply by ignoring the mental health issues of this patient and refusing to ask his loved ones, all of whom knew the correct story.

Nancy Verdin

May 26, 2023 2:30 PM

I have done HHD for 21 years, nocturnal for the first 13. I had a "wet" alarm for the first 6 months, that did not respond to a leak because there was too much gauze between the sensor and the leak. It was the leak itself the woke. I stopped using the alarm. And addressed the leaking needle site instead. I was using a button hole with a sharp needle, I switched to blunt needle and the leak stopped.

Comment about leaving the arm exposed ... have you ever spent a) four hours freezing through a treatment, it takes one energy, one can't focus on reading or TV hence a rough length of time to do at least 3 days a week. Rather than keeping the arm exposed how about checking the sites with each blood pressure? The patient may be able to tell there is a leak as it is an odd sensation against the skin. b) have you every held your arm out, with out moving for 4 hours. Think about from our side ...

When it comes to problem solving around potential problems please think about and ask about the patient experience .... we have lots of answers if people will listen and teaching us with fear of death is not constructive to building peoples confidence to doing HHD.

Thank you for the forum that let's me share my ideas.

Nancy